In a landmark study published in Nature Communications, scientists from Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) unveiled a groundbreaking technique to create functional human eggs from skin cells. This novel approach could one day help women with dysfunctional eggs have genetic children of their own.

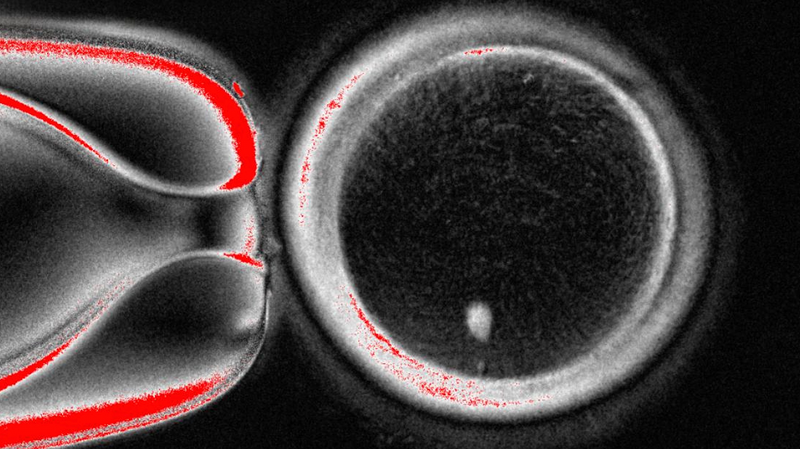

The team's technique involves removing the nucleus from a donor oocyte and replacing it with the nucleus from a woman's skin cell. To tackle the challenge of duplicate chromosomes found in non-reproductive cells, researchers developed a third mode of division – mitomeiosis – that mimics how eggs naturally eject extra genetic material.

"We achieved something that was thought to be impossible," said Shoukhrat Mitalipov, lead author and head of the OHSU Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy. "Nature gave us two methods of cell division, and we just developed a third."

In one experiment, 82 modified eggs were fertilized with sperm in vitro. About 9% developed to the blastocyst stage – when embryos consist of 70 to 200 cells and are ready for transfer in fertility treatments. Nevertheless, none progressed beyond this point, and most stopped growing at the 4- to 8-cell stage, often showing chromosomal glitches.

"Doctors are seeing increasing numbers of people who cannot use their own eggs, often because of age or medical conditions," noted reproductive medicine specialist Ying Cheong of the University of Southampton, who was not involved in the study. Roger Sturmey, a specialist at the University of Hull, added that persuading non-reproductive cells to undergo egg-like division is a remarkable feat, even if clinical use remains distant.

The researchers agree that refining the technique will require at least a decade of additional work to ensure safety and effectiveness. They emphasize that rigorous testing and regulatory approval are critical before considering clinical trials.

While still in its infancy, this breakthrough offers fresh insights into infertility and miscarriage. As the science progresses, it could open new paths for creating egg- or sperm-like cells, providing hope for those with limited reproductive options around the world.

Reference(s):

cgtn.com