NATO defense ministers convened in Brussels this Thursday and agreed on a bold target: raise military spending to 5% of GDP. But deep divisions over deadlines and spending categories threaten to overshadow the push ahead of the June 24-25 summit in The Hague.

A push for 5% GDP

At the heart of the debate lies a compromise plan from NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte to split the 5% goal into 3.5% for core military capabilities and 1.5% for broader security areas such as infrastructure and logistics by 2032. “There’s broad support. We are really close,” Rutte told reporters, adding he had “total confidence” the alliance would seal the deal by the next summit.

US Pressure and Strategic Urgency

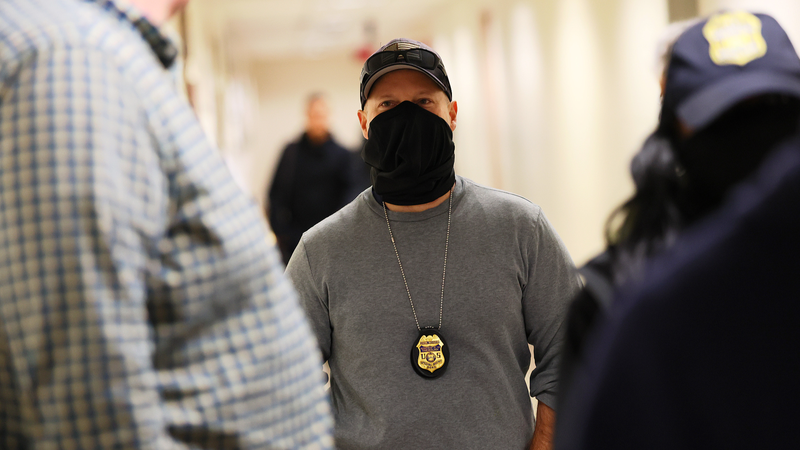

The United States has been the biggest driver behind the push, first proposing the 5% benchmark late last year. U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth underscored the stakes as he arrived in Brussels: “To be an alliance, you got to be more than flags… keep combat-ready capabilities.” Acknowledging some holdouts, Hegseth said, “There are a few countries that are not quite there yet… We will get them there.”

Timeline Tensions and Spending Splits

Divisions flared over the 2032 deadline. Lithuania’s Defense Minister Dovile Sakaliene called 2032 “definitely too late” and pushed for a 2030 target. Estonia’s Hanno Pevkur noted Estonia would hit 5% by next year and urged peers to follow suit within five years.

On the other hand, Spain, Germany, and Belgium warned meeting the 5% goal is “extremely difficult” under current budgets and industrial limits. The UK and Italy offered a more moderate plan: raise core defense spending to 3.5% of GDP by 2035.

According to NATO data, 23 of 32 members are set to meet the 2% GDP defense threshold by summer’s end. Spain and Italy aim for year-end compliance, and Canada projects reaching the mark by 2027.

Capability Goals vs. Budget Realities

Ministers also approved updated NATO capability targets, focusing on air and missile defense, long-range strike, logistics, and large-scale land maneuver forces. Germany pledged to reinforce its contribution with 60,000 active-duty troops. “Given Germany’s size and economic strength, we will shoulder a significant part of NATO’s military build-up,” said Defense Minister Boris Pistorius. Yet Berlin still faces personnel shortages, with troop numbers falling last year and the average age of soldiers rising.

National budgets add another layer of complexity. The Netherlands estimates it needs an extra €16–19 billion annually to meet its obligations. Belgium’s Budget Minister Vincent Van Peteghem warned, “Every euro that’s a deficit today … will be debt, and that debt will become a tax or a cut in the social welfare state. Defense definitely requires our full attention, but so does the sustainability of our welfare state.”

The Road to The Hague

With the June 24-25 summit in The Hague looming, NATO faces a critical test: can member states reconcile ambitious defense goals with fiscal realities? As capitals crunch the numbers, the alliance’s unity—and its collective security—hangs in the balance.

Reference(s):

NATO defense ministers struggle to bridge divides over defense budget

cgtn.com