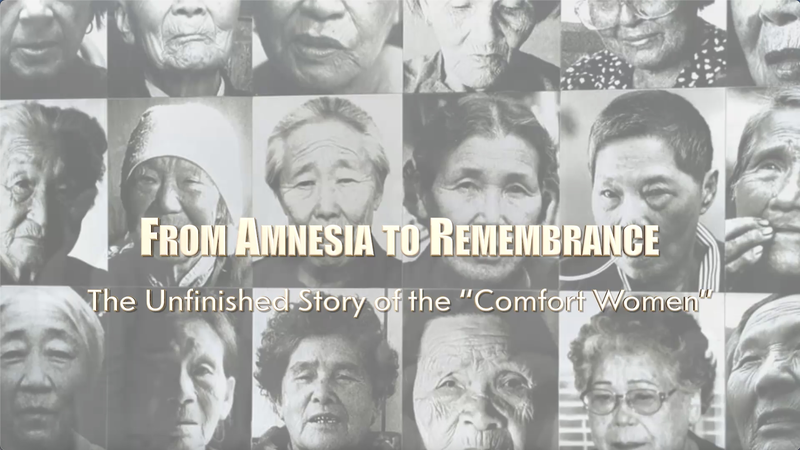

More than 80 years after World War II, a dark legacy of forced sexual slavery by Japan’s military remains unresolved. An estimated 400,000 women from China, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and beyond were conscripted into the so-called “comfort women” system. Many died or suffered lifelong trauma, their stories buried until 1991, when South Korean survivor Kim Hak-sun broke decades of silence, inspiring thousands to speak out.

Today, fewer than 50 survivors remain worldwide. In Yueyang City on the Chinese mainland, 96-year-old Peng Zhuying demands a formal apology. She says, “I demand the Japanese government acknowledge its wartime crimes and issue a formal, unreserved apology.” Her plea underscores the urgency for recognition before it’s too late.

Unearthing a Buried History

Historian Su Zhiliang of Shanghai Normal University has led a decades-long effort to recover testimonies and archival records. Since establishing the Research Center on the “comfort women” issue in 1999, his team has identified over 300 survivors in the Chinese mainland, collected diaries, letters and official documents proving the Japanese military’s involvement in the system.

“There is a large body of evidence showing that the Japanese government and military were actively involved in implementing this system,” Su says. Among the findings was a 1940s Korean community registry in Jinhua listing 126 young women with no occupations, all linked to a known comfort-station owner.

The center also founded the Chinese “Comfort Women” History Museum in Shanghai, a monument built on survivors’ testimonies. Beyond exhibitions, it runs a relief fund providing health care, living stipends and burial costs, and supports survivors in appealing to UNESCO for recognition.

UNESCO’s Bid to Preserve History

In 2016, civil society groups from eight countries and regions submitted the “Voices of the Comfort Women” archive to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. A rival nomination denying forced slavery led UNESCO to suspend both bids in 2017 and call for dialogue.

Heisoo Shin, director of the joint nomination’s secretariat, recalls political pressure: “The Japanese government threatened to withdraw its membership or contributions,” complicating UNESCO’s decision. More than eight years later, the listing remains in limbo, prolonging survivors’ quest for global acknowledgment.

Global Solidarity and Ongoing Struggle

The legacy of the comfort women has spurred global activism. The Statue of Peace in South Korea, now in cities from New York to Berlin, symbolizes survivors’ demands for apology and compensation. Weekly vigils in front of Japanese diplomatic missions draw crowds in Seoul and Busan. In Southeast Asia, survivors and advocates have filed lawsuits and formed support networks.

UN human rights reports since the 1990s have condemned the comfort women system as “sexual slavery,” urging Japan to apologize and make amends. Parliaments in the United States, Canada and the Netherlands passed resolutions demanding official acknowledgment. Japan’s official resistance fuels activists’ resolve to continue pressing for justice.

Remembrance and Legacy

As survivors age, younger generations carry the torch. PhD candidate Zhang Ruyi argues, “We must speak internationally to ensure the world remembers these victims.” In the Philippines, survivors like the late Lola Estelita Dy hoped their stories would teach future generations to oppose war and protect human dignity.

The story of the comfort women is still unfinished. Their voices remind us that recognition, apology and reparations are not just historical lessons—they are living calls for justice and peace.

Reference(s):

From amnesia to remembrance: Unfinished story of the 'comfort women'

cgtn.com